Evolution of LUPINS and Continental Drift

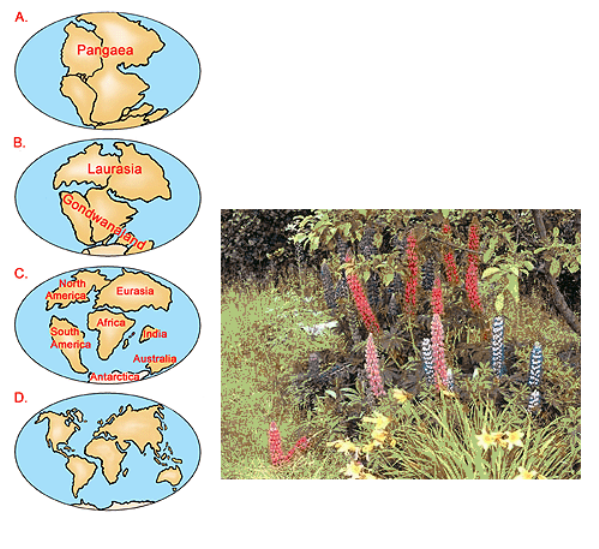

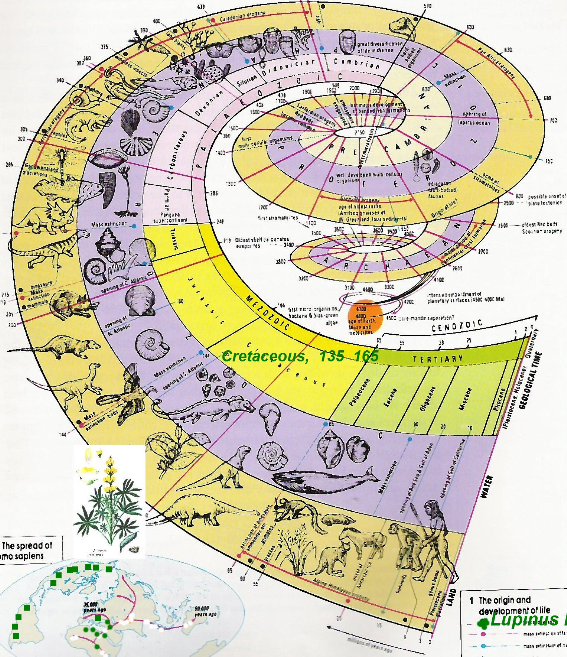

Wegener's theory of continental drift suggests a hypothesis about stage-by-stage division of continents in the past two hundred and fifty to fifty million years. Similar plant and animal fossils are found around different continent shores, suggesting that they were once joined.

According to this hypothesis the unified primary centre of formation for most ancient ancestors of lupin probably existed in the Cretaceous and subsequent periods on Laurasia. Further on, as a result of subsequent division of the continents, the development of remote ancestors of lupin continued independently on the divided parts. It was homologous but not identical, pursuant to the Vavilov’s law of homological series.

Evolution of ancient ancestors of Lupins in the couse of drift of continents

Fast development and seizure of new biotic spaces by angiospermous vegetation started in the Cretaceous period. There were many families of angiospermous plants at that time, including the genus Lupinus. Proceeding from this thesis, it is possible to surmise, that a considerable proportion of ancient progenitors of lupins appeared also in the Cretaceous period in Laurasia, and predominantly, in its western part, which subsequently turned into North America. It is confirmed by today’s presence on the American continent of a large number of species. Further distribution of lupins, or their progenitors, from the north to the south, in particular from North America into Central and even South America and from Northern Europe into the countries of the Mediterranean and Africa, could have been provoked by periodically recurring changes of climate, chill and thaw, seismic activity or oscillations of the magnetic field.

The origin and development of Live

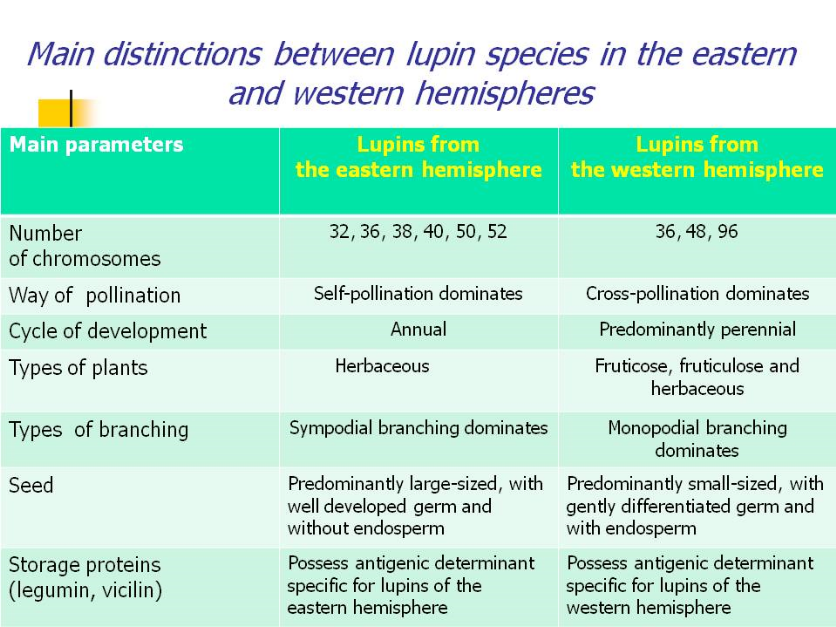

When the continents drifted apart, however, lupin ancestors found themselves in isolated environments and started their independent development. The species of lupin currently existing in both hemispheres, already emerged after the splitting of the continents. It explains the existence of two absolutely isolated lupin groups differing in morphological characters, development cycles, sets of chromosomes and having a genetic barrier against crossing.

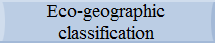

American lupin forms are somewhat less specialized than Mediterranean ones. They are characterized by a more primitive monopodial type of branching and by the cross-pollination habit (with the help of insects). Their plants are heterozygous and easily generate all possible mutations. Seeds are small, the embryo is gently differentiated, it is insufficient in endosperm and located close to the seed cover, with a lengthened hypocotyl. Rather specialized Mediterranean lupin forms are characterized by a more advanced type of branching (sympodial); for them, self-pollination is dominating. Seeds are larger, the embryo is well-formed, with two sedentary leaves or a very short hypocotyl.

Lupins from the Mediterranean region and those from America are also contrasting in storage proteins, each of the groups having determinants specific for their native hemisphere. These distinctions between lupins of the two continents have induced us to search for a more accurate definition of their systematic position in the generic system.

Considering the essential morphological differences between lupins of the two hemispheres, we made revision of two subgenera in Lupinus L., according to geographic principle. The genus Lupinus L. and, in particular, its North-American species, were divided by Watson (in 1873) into three parts: Lupinus, Platycarpos and Lupinnelus. Differences in habit and in the number of ovules were accepted as the basis for this classification. The majority of perennial and annual species from the American continent described by Watson was referred to Lupinus.

To the Platycarpos section were attributed some annual species with two ovules in the ovary, and two seeds in the pod (L. densiflorus , L. micricarpus).

Section Lupinnelus consisted of one species (L. uncialis), with axillary and solitary flowers, and also with two ovules in the ovary. Presently, the existence of such species seems doubtful.

This principle of classification was extended by Ascherson and Graebner to all lupins from the eastern and western hemispheres. The genus Lupinus was for the first time subdivided into two subgenera: A. Eulupinus and B. Platycarpos. Quantity of ovules (seed buds) in the ovary and seeds in the pod was also accepted as the criterion for this division. Majority of the described species from the eastern and western hemispheres were referred to subgenus A. Eulupinus. Subgenus B. Platycarpos included several annual species from the eastern hemisphere with two seedbuds and seeds in the bean. (The same species, as the one specified by Watson).

These works were a starting point for our researches.

In connection with definition of two secondary centres of formation for different species of lupin in the eastern and western hemispheres, and with the essential morphological differences between lupins of the two hemispheres (Table), we managed to revise the volumes of two subgenera in the genus Lupinus according to the geographic principle, however in view of the findings of the previous writers (Kurlovich, 1989).